Abstract

Although we have literature on treatment options for glaucoma in pregnant women, doubts about which medical treatment can be safer and the proper management of glaucoma during pregnancy persist to this day 1 . In a survey published in 2007 in the magazine Eye, 26% of respondents reported having treated a pregnant woman with glaucoma. This theoretically infrequent situation is becoming less frequent and in daily clinical practice we find women of childbearing age with glaucoma who raise concerns about the treatment they need for their illness and possible complications during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Advances in medical and surgical treatment of congenital and childhood glaucoma have contributed to this, as they have allowed patients to reach adulthood with good visual function.

It is estimated that during pregnancy the IOP is reduced by up to 10%, with this decrease being more pronounced in the third trimester. The cause seems to be multifactorial, the hormonal alteration being the most important one, which conditions the increase in the outflow of aqueous humor and the decrease in the episcleral venous pressure 2 . However, the evolution of glaucoma during pregnancy is variable, despite this theoretical hormonal protective factor 3,4 . Most patients remain stable during pregnancy, while a small percentage, approximately 10%, may have increased IOP or disease progression 3 .

The impossibility of conducting studies means that we have to resort to clinical case series for more information on the management of glaucoma during pregnancy. In a retrospective study on 28 eyes of 15 women published 6 years ago, 57.1% of the eyes studied (16 eyes in total) did not progress and maintained stable IOP during pregnancy 4 and despite this natural tendency to decrease IOP, cases have been described in which there was disease progression during pregnancy 3-7. Many of these women are diagnosed with congenital glaucoma and childhood glaucoma or that are developmentally triggered. Others have inflammatory or pigmentary glaucoma. In many cases, we find women who have a significant reduction in the visual field in at least one of the 2 eyes and who have undergone multiple surgical interventions. It is possible that in these types of glaucoma, which are the most common in childbearing age, the behavior of IOP is not the same as observed in primary open-angle glaucoma or in healthy women in whom IOP was studied. Behavior of IOP during pregnancy.

One of the difficulties in treating glaucoma in pregnancy is the need to maintain visual function in patients with advanced visual field defects, in light of careful consideration of the potential risks of medical or surgical treatment to both the mother and the patient.

The decision to treat or not and the type of medication to use involves individualizing each case. The available treatment options for glaucoma (physician, laser trabeculoplasty, or surgical treatment) are more limited in these cases. It would be advisable to anticipate the pregnancy as much as possible and explain to the patient the importance of notifying the ophthalmologist as soon as possible in order to control the IOP with as few drops as possible.

There are no studies that guarantee 100% fetus safety. For this reason, it is recommended to suspend medical treatment in the first trimester, the period of greatest risk for fetal malformations.

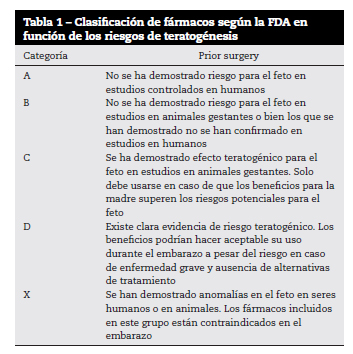

In cases where the establishment of medical treatment is necessary, both the side effects that may occur due to the transfer of the drug to the fetus when crossing the blood-placental barrier, as well as the possible effects on uterine motility and the consequent risk of prematurity, birth or miscarriage. According to the FDA's safety classification based on experimental models ( Table 1), brimonidine belongs to category B, ie no adverse effects on the fetus have been demonstrated in animal studies. There are no human studies. The rest of the antiglaucoma drugs (prostaglandins, β-blockers, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, cholinergics...) belong to category C, that is, adverse effects on the fetus have been demonstrated in controlled studies in animals, although there are no studies or there is no evidence in humans. Brimonidine may be considered the safest drug during pregnancy as it is the only one included in category B. However, this drug not only crosses the blood-brain barrier, producing CNS depression and apnea in young children, but it can also cross the blood-placental barrier.

The first-line drugs in glaucoma, the prostaglandins, belong to the group of category C drugs. The prostaglandin F2α analogues have oxytocic and luteolytic activity and may predispose to spontaneous abortion 8,9 , although experimental studies in animals have not found an effect on embryo at doses up to 15 times higher than therapeutics in humans 10 Although there are case series in which the use of latanoprost during pregnancy was not associated with premature births or abortions 11 , the ability to cross the blood-placental barrier and the fact that may affect uterine motility with the risks that this implies not recommending its use during pregnancy.

Topical β-blockers can cause bradycardia and arrhythmias in the fetus. However, obstetrics specialists have been using β-blockers as antihypertensive drugs for years in hypertension developed during pregnancy 12,13 . Its commercial gel form with a lower concentration (0.1%) is a safer treatment option. Due to the greater experience in the use of these drugs during pregnancy, we consider it to be the drug of first choice.

Oral treatment with carbonic anhydrase inhibitors has been associated with the development of sacrococcygeal teratomas in the newborn, although no adverse effects have been reported with topical treatment. Recently, intrauterine growth retardation requiring cesarean delivery was described in a woman with congenital glaucoma who continued topical treatment during pregnancy with the fixed combination of timolol-dorzolamide 3 .

At our center, we try to keep the patient off topical treatment during the first trimester to avoid the risk of teratogenesis. In cases where treatment is necessary due to the risk of progression, the first therapeutic option is a topical β-blocker, preferably timolol in its gel formulation, followed by topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Whenever possible, we keep the patient under observation and without medical treatment or with as few medications as possible during the first trimester and the last month of pregnancy. In all cases, we ruled out the use of prostaglandins because, although there are retrospective studies in which no side effects have been demonstrated for the fetus.

Some authors believe that the lack of information about the safety of antihypertensive drugs during the therapeutic approach to pregnancy makes it another necessity to include laser treatment or surgery.

Laser trabeculoplasty allows IOP to be kept within normal limits with fewer hypotensive drugs. It can be a good alternative treatment as long as the angle morphology allows it, something unusual in the types of glaucoma that women of childbearing age have. Laser trabeculoplasty is not as effective in these cases due to the present angular alterations, inherent to the disease itself, or due to the presence of angular synechiae. Inflammatory glaucomas that are congenital or developed during childhood as a result of anterior chamber malformations such as Rieger syndrome, Peters syndrome, Axenfel syndrome, or aniridia tend to have a compromised angle, so the results of ALT or SLT are more limited.

The use of diode cyclodestruction in pregnancy has recently been described. The goal of treatment would be to reduce IOP with as few drugs as possible before planning the pregnancy 6 . Treatment can be done under local anesthesia and can be repeated in case of insufficient IOP control. Anatomical differences in terms of morphology and position of the ciliary body in congenital and childhood-developed glaucomas should be taken into account, as well as possible complications in patients with thin sclera or inflammatory glaucomas.

The surgical difficulty in these cases is greater, as we are often found in patients who have undergone repeated operations and with an angular compromise that limits the type of surgery. In the case of hypertensive peaks, the risk of visual loss requires the decision to filter surgical treatment with local anesthesia and avoid antimetabolites. On the other hand, it is advisable to keep the patient in lateral decubitus to avoid vena cava compression and gastroesophageal reflux, especially in the third trimester.

Regarding the use of hypotensives during lactation, we know that their passage into breast milk has been demonstrated 14,15 . Regarding safer hypotensives during lactation, we consider the same therapeutic options we apply during pregnancy, using timolol gel as a first-line drug. To reduce the amount of medicine that passes to the newborn, the drops can be instilled immediately after ingestion and the punctum occluded for 5 minutes, although it is advisable to stop breastfeeding if there is a need for anti-glaucoma treatment.

In summary, in cases where medical treatment is needed, the pros and cons of treatment should be properly evaluated on an individual basis, with no hypotensive treatment during the first trimester, and only the safest medications for the mother and baby should be considered fetus, topical β-blockers and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors performing punctal occlusion to reduce systemic absorption. It is advisable to stop medical treatment weeks before the expected date of delivery.

References

Vaideanu D, Fraser S. Gestão do glaucoma na gravidez: um inquérito por questionário. Olho. 2007; 21: 341-2. [ Links ]

Ziai N, Ory SJ, Khan AR, Brubaker RF. Beta-gonadotrofina coriônica humana, progesterona e dinâmica aquosa durante a gravidez. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994; 112: 801-6. [ Links ]

Mendez-Hernandez C, Garcia-Feijoo J, Saenz-Frances F, Santos Bueso E, Martinez-de-la-Casa JM, Valverde Megias A, et al. Efeitos da terapia tópica de pressão intraocular na gravidez. Oftalmologia Clínica. 2012; 6: 1629-32. [ Links ]

Brauner SC, Chen TC, Hutchinson BT, Chang MA, Pasquale LR, Grosskreutz CL. O curso do glaucoma durante a gravidez: uma série de casos retrospectivos. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006; 124: 1089-94. [ Links ]

Johnson SM, Martinez M, Freedman S. Management of glaucoma in pregnation and lactation. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001; 45: 449-54. [ Links ]

Wertheim M, Broadway DC. Terapia a laser ciclodiodo para controlar a pressão intraocular durante a gravidez. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002; 86: 1318-9. [ Links ]

Coleman AL, Mosaed S, Kamal D. Medical therapy in pregning. J Glaucoma. 2005; 14: 414-6. [ Links ]

Salamalekis E, Kassanos D, Hassiakos D, Chrelias C, Ghristodoulakos G. Administração intra / extra-amniótica de prostaglandina F2a em morte fetal, abortos perdidos e terapêuticos. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 1990; 17: 17-21. [ Links ]

Lipitz S, Grisaru D, Libshiz A., Rotstein Z, Schiff E, Lidor A, et al. Prostaglandina F2 alfa intraamniótica para interrupção da gravidez no segundo e no início do terceiro trimestre da gravidez. J Reprod Med. 1997; 42: 235-8. [ Links ]

Chang MC, Hunt DM. Efeito da prostaglandina F2 alfa na gravidez precoce de coelhos. Natureza. 1972; 236: 120-1. [ Links ]

De Santis M, Lucchese A, Carducci B, Cavalieri A, de Santis L, exposição Merota A. Latanoprost na gravidez. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004; 138: 305-6. [ Links ]

Wide-Swensson D, Montal S, Ingemarsson I. Como obstetras suecos gerenciam distúrbios hipertensivos na gravidez: um estudo por questionário. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1994; 73: 619-24. [ Links ]

Gladstone GR, Hordof A, Gersony WM. Administração de propranolol durante a gravidez: efeitos no feto. J Pediatr. 1975; 86: 962-4. [ Links ]

Fidler J, Smith V, de Swiet M. Exccretion of oxprenolol and timolol in breast milk. Ir. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1983; 90: 961-5. [ Links ]

Salminen L. Revisão: absorção sistêmica de drogas oculares aplicadas topicamente em humanos. J Ocul Pharmacol. 1990; 6: 243-9. [ Links ]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Copyright (c) 2021 Maria Luiza Viana Maia